The Female SOE Agents of World War II

For the past few months, I, like many other Czech gymnasium students, have been attempting to write a social studies seminar paper. My topic is the relationship between feminism and fashion, and in this edition of the Gustav English corner, I thought I would share with you something I learned about World War II during the research phase of my seminar work. To be more precise, I would like to inform you about the female agents of the British Special Operations Executive (SOE).

This organization, headquartered at 64 Baker Street in London, was formed in 1940 right after Prime Minister Winston Churchill pledged the United Kingdom’s support for the resistance movement. The SOE’s official purpose was to put British special agents on the ground in continental Europe to coordinate, inspire and assist the citizens of the oppressed countries. The “Baker Street Irregulars,” as they came to be known, were trained in small arms, sabotage, radio and telegraph communication, and unarmed communication. The SOEs were also required to be fluent in the language of the nation in which they were to be inserted, the goal being for them to fit in seamlessly. If someone learned about their presence or became suspicious of them, their mission could be over before it even began.

In the British forces, women proved irreplaceable as spies, curriers, saboteurs, and radio operators in the field. Though some people weren’t pleased with sending women behind enemy lines, they agreed that female spies would have certain advantages. Gender stereotypes helped minimize suspicion, for who would think a WOMAN could be skilled in combat?

The female spies of the SOE were successful because they learned how to become unnoticeable. They took on secret identities, were trusted with their country’s biggest secrets, and went on secret missions. During the war, there were 39 female SOE agents stationed in France, while 16 were in other European countries.

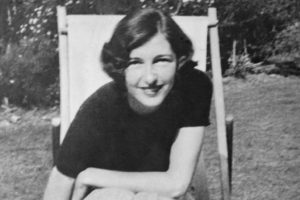

Nancy Wake was one of these 39 female SOEs. The Gestapo called her “ the white mouse“ because she always managed to escape capture. When she learned one of the resistance groups no longer had radio communication, she rode almost 300km on a bike to make radio contact with her SOE headquarters and arrange for an equipment drop. Despite many of Nancy’s brushes with death, she managed to survive the war.

Other women weren’t as lucky. Noor Inayat Khan, known as Madeleine, was the only active SOE radio operator in the Paris area during 1943. While her colleagues were getting captured, she moved from safe house to safe house daily, lugging her wireless radio transmitter on her back. After she and her team were captured by the Gestapo, Noor didn’t break during the interrogations and tried repeatedly to escape. In 1944, she was sent to Dachau and executed upon arrival.

Virginia Hall was another one of Churchill’s recruits. Ironically, she wasn’t even British. The feisty American redhead was living in France when the war broke out. What makes her unique is that she had a wooden foot, the result of a pre-war hunting accident, but she was recruited by the SOE nevertheless and became an undercover journalist for the New York Post. In 1942, she escaped the Lyon Gestapo by crossing the Pyrenees on foot into Spain. After Virginia made her way back to London, she became an OSS agent (basically the American equivalent of the SOE) and was once again in 1944 put ashore in France. There, she assisted resistance groups until D-Day. After the war, she served in an offshoot of the OSS – the CIA.

Christine Granville, who was in fact the Polish countess Krystyna Skarbek, parachuted into Vercors, France in 1944. She worked in one of the SOE’s most successful circuits and bravely rescued the circuit leader and two colleagues from the Gestapo. After the war, she became friends with Ian Fleming, a wartime intelligence officer, and because of her charm, colorful personality, and courage, became his inspiration for the first James Bond heroine – Vesper Lynd. Fleming wasn’t the only man she enchanted; Christine was said to be Churchill’s favorite spy.

Lastly, and closer to home, Haviva Reik was a Slovak Jewish refugee who enlisted in the SOE and returned to Slovakia in 1944, where she organized a Jewish resistance unit in the mountains near Banská Bystrica. The unit being Jewish provoked a decisive Nazi response. Their camp was overrun, and Reik was captured and executed.

These are just some of the stories of the female SOE agents. These ordinary women, of all ages and stations, managed to execute the most extraordinary acts of bravery. When the war was over, the survivors returned to the shadows, blended in seamlessly with society, and did not seek attention, thinking they had simply done their part. Most were never recognized for their efforts, but they certainly should be.

Halina Bellová

- Haviva Reik

- Christine Grandville

- Nancy Wake

- Noor Inayat Khan

- Virginia Hall